This article was updated August 24, 2020.

Producers and consumers place great value on where their wine grapes are grown. The famous wine-grape producing areas—such as Napa Valley, California, and Walla Walla, Washington— have come to be publicly associated with quality.

However, many wineries are surprised to learn this perceived quality can be quantified and used to offset tax liabilities in the years following a vineyard purchase. The more prestigious the land area, the greater the potential savings.

This complex process includes an American Viticultural Area (AVA) valuation, and the potential tax savings can be significant. Here’s what wineries and vineyard owners need to know about the process to potentially benefit from the savings opportunity.

An AVA is a geographic area where wine grapes are produced, as defined by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB). As of June 3, 2020, there are 248 established AVAs in the United States, with 139 in California.

An AVA may have an intangible value associated with the quality of the grapes produced within it. Unlike land, producers may be able to amortize the value of this asset for tax purposes, but doing so requires a valuation to determine the intangible value of the AVA.

Simply put, the intangible value of a production area results from the perceived value of the wine and wine grapes produced there. This value comes from a number of factors, such as established root stock, weather, soil quality, and consumer preference.

Wineries are only allowed to claim their wine was produced in an AVA if the following conditions are met:

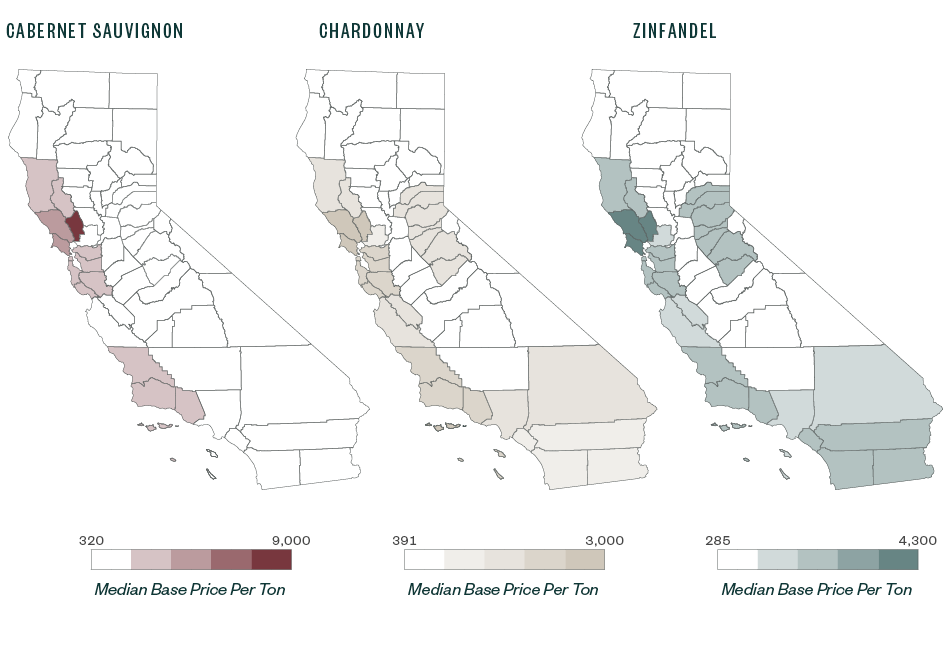

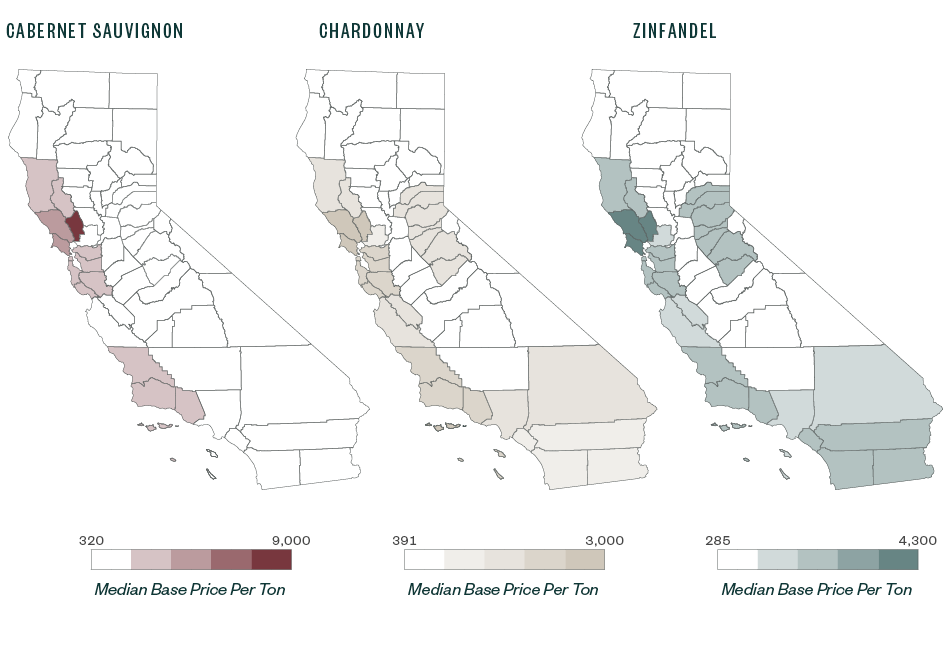

Prices paid for grapes from different regions can vary dramatically. The graphs below illustrate 2019 bulk grape pricing in California, as reported by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for different crush districts.

For example, in the Cabernet Sauvignon grape pricing chart, in district four—which is Napa County—the median price of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes was approximately $9,000 per ton.

This can be compared to the median of district 10—which includes the Sierra Nevada Foothills counties such as El Dorado and Amador—where the median price for Cabernet grapes was $1,625 per ton.

When a buyer purchases a vineyard, the AVA intangible creates a potential tax savings by amortizing the AVA value in the 15 years after the purchase occurs.

If an AVA intangible isn’t measured at the time of a purchase, an AVA valuation can still be performed and the amortization expenses can be retroactively applied to recognized deductions not taken in prior years.

Amortization is the gradual recognition in income of a capital expense over a specific period of time. It’s typically associated with intangible assets—like trademarks—or, in this case, AVAs.

Essentially, it expenses the intangible value of the AVA associated with the land. This option allows vineyard owners to put some of the money they’ve spent to acquire land in a highly desirable AVA back into their businesses.

If you purchase a vineyard, you can’t depreciate or amortize the value of the land used to grow the grapes. There’s a distinct separation between the AVA value and the value of the land.

Quantifying the AVA value happens through a complex process known as an AVA valuation. The resulting amount is what vineyards are able to claim for amortization.

There are a few different methods used to determine the potential AVA value.

This method involves looking at two scenarios comparing vineyards producing the same grapes of similar quality. One vineyard is within a particular AVA, and one isn’t.

By comparing different prices of the grapes produced in each area and the subsequent effect on projected cash flows from the vineyards, the AVA’s intangible value can be calculated.

Estimating a hypothetical avoided royalty or licensing fee is a common way to value tradenames. Distinguishing that a wine is made with grapes from a specific AVA is much the same as marketing that wine with a specific trademark.

While we know AVA designations can’t be licensed, wine brands, as well as brands for other similar products, can be. Comparing the licensing and royalty fees that might be paid by wineries wishing to use different brand names on their packaging offers many insights into the potential value an AVA designation could offer.

Generally, the more profit a winery can produce by licensing a brand, the higher the value of the associated intangible asset.

Also known as the market approach, comparing the sale records of different vineyards offers an indirect way to quantify the effects of an AVA designation on land value.

While the price of vineyards can be impacted by many factors, these designations can have a significant impact on comparative vineyard value. The goal is to separate the cost of the land from the value provided by the AVA designation.

With owners making claims about AVA value due to the potentially significant tax savings, the IRS and states are increasing scrutiny on these claims. The larger the claim, the more likely an examination could occur.

Making a well-supported claim should be the ultimate goal. Utilizing multiple valuation methods, providing the appropriate documentation, and working with an advisor with deep industry expertise can help the process move smoothly.

For more information about AVA valuations and how they could help your winery save money, contact an accounting or consulting professional.