Work–Life Balance and Life Satisfaction in OECD Countries: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

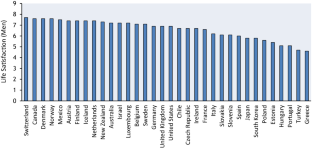

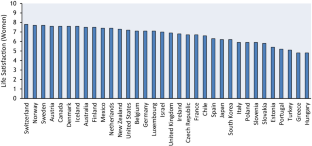

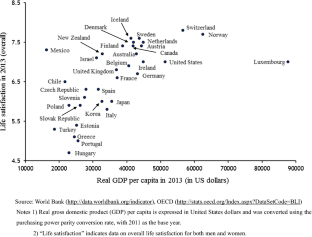

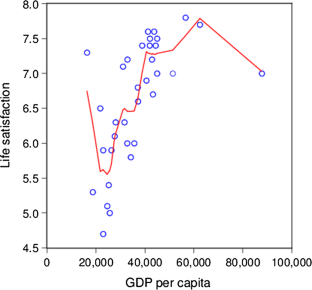

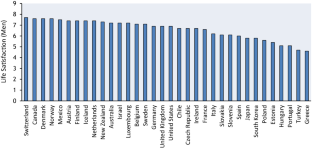

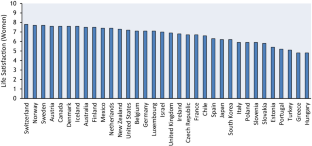

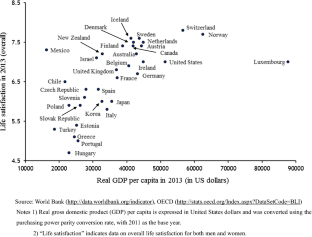

Work–life balance, as an effort to achieve a balance between work and personal (family) life, has been a key area of concern in labor policies since the early 2000s. One factor contributing to this trend is the implicit assumption that implementing a work–life balance policy increases people’s life satisfaction. The association between work–life balance and life satisfaction, however, is not self-evident. In this article, we investigate the effect of work–life balance on life satisfaction using data on men and women in OECD countries. A cross-sectional analysis suggests that implementing work–life balance policy leads to the improvement of life satisfaction for both men and women. However, the work–life balance elasticity of life satisfaction—the percentage change in life satisfaction in response to a 1% change in the level of work–life balance—is greater for men than for women. Conventionally, work–life balance issues have predominantly been thought to concern women rather than men. The present results imply that institutional design that adequately incorporates the work–life balance of both men and women is important for increasing life satisfaction.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save

Springer+ Basic

€32.70 /Month

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Buy Now

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Similar content being viewed by others

Economic Growth and Work–Life Balance

Chapter © 2021

Well-Being and the Labour Market from a Global View: It’s Not Just the Money

Chapter © 2015

Bad Jobs Versus Good Jobs: Does It Matter for Life and Job Satisfaction?

Article 30 May 2023

Explore related subjects

Notes

For example, Karkoulian et al. (2016) noted that, given the crucial role that work–life balance plays in the well-being of employees, existing studies have devoted extensive research efforts to determining the effects of different variables on the quality of employees’ work–life balance.

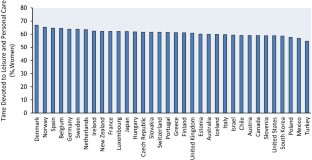

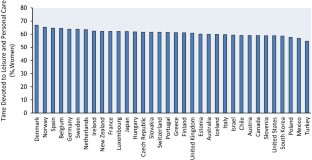

In the OECD Better Life Index, time devoted to leisure and personal care is expressed in hours per day rather than as a percentage of time devoted to these pursuits. In the present study, these values were divided by 24 and expressed as percentages of time devoted to leisure and personal care in one day. Here, “leisure” includes sports activities, participating in and attending events, visiting or entertaining friends, watching television, listening to the radio at home, and other leisure activities. “Personal care” is defined as activities such as sleeping; eating and drinking; personal, household, and medical services; and travel related to personal care (OECD 2011b).

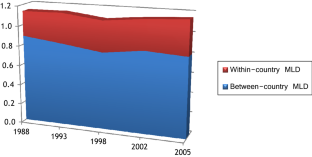

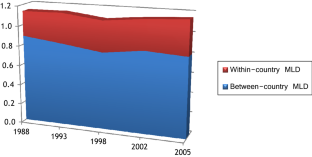

Among the numerous empirical studies on income inequality conducted in the past, examples of major studies published in journals after year 2000 include Bourguignon and Morrison (2002) and Sala-i-Martin (2006). These studies have used various indicators to conduct detailed examinations of the unequal distribution of personal income on a global scale. Helpman (2004) has provided a simple and concise survey of existing empirical research on income inequality.

Oshio and Kobayashi’s (2011) findings appear to be analogous to Alesina et al.’s (2004) results for Europe, which showed that inequality resulted in a loss of happiness among poor people.

Oshio and Urakawa (2014) demonstrated that perceived income inequality, rather than actual inequality, was associated with subjective well-being, using cross-sectional data collected from a nationwide, Internet survey conducted in Japan. Their empirical results supported the hypothesis that subjective assessments of income inequality affects individuals’ subjective well-being, that is, perceived income inequality was negatively associated with subjective well-being.

Szücs et al. (2011) found that satisfaction with work–life balance and overall life satisfaction were closely related in European countries. Specifically, the greater the satisfaction with the work–life balance, the greater the overall life satisfaction. They concluded that organizational and personal initiatives intended to improve individuals’ ability to balance work and non-work roles may increase not only satisfaction with work–life balance, but also general life satisfaction, which would contribute to a higher quality of life.

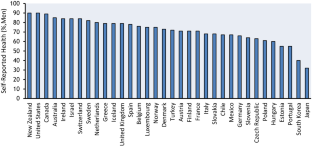

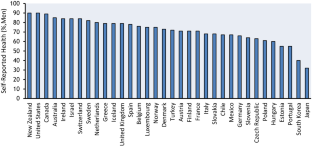

Frey (2018) noted that objective evaluations of health by medical doctors were less strongly correlated with life satisfaction, although subjectively perceived good health and subjective life satisfaction are closely related.

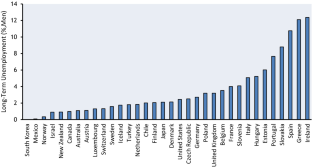

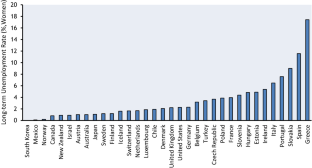

Helliwell and Huang (2014) showed that, for people who were employed, a one percentage point increase in local unemployment had an impact on well-being roughly equivalent to a 4% decline in household income, based on large United States surveys.

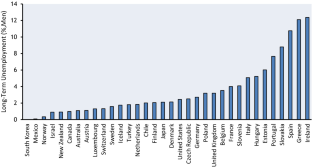

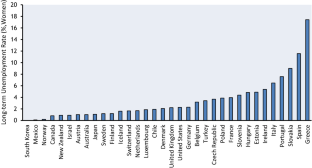

Using data on 10 European countries, Ochsen and Welsch (2011) found that the social costs of unemployment, in terms of its impact on life satisfaction, are related to the duration of unemployment. Specifically, reducing long-term unemployment may have a stronger impact on well-being than would reducing the number of people who are unemployed at any point in time. Therefore, these researchers highlighted the importance of labor policies on long-term unemployment.

According to Kyo et al. (2013), structural and frictional factors accounted for approximately 60% of overall unemployment in Japan, in terms of the average from January 2010 to January 2011.

References

- Abendroth, A.-K., & Den Dulk, L. (2011). Support for the work-life balance in Europe: The impact of state, workplace and family support on work-life balance satisfaction. Work, Employment and Society,25(2), 234–256. Google Scholar

- Adame, C., Caplliure, E.-M., & Miquel, M.-J. (2016). Work-life balance and firms: A matter of women? Journal of Business Research,69(4), 1379–1383. Google Scholar

- Adame-Sánchez, C., González-Cruz, T. F., & Martínez-Fuentes, C. (2016). Do firms implement work-life balance policies to benefit their workers or themselves? Journal of Business Research,69(11), 5519–5523. Google Scholar

- Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics,88(9–10), 2009–2042. Google Scholar

- Anand, S., & Segal, P. (2015). The global distribution of income. In A. B. Atkinson & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2A, pp. 937–979). Amsterdam: Elsevier. (Chapter 11). Google Scholar

- Anttila, T., Oinas, T., Tammelin, M., & Nätti, J. (2015). Working-time regimes and work-life balance in Europe. European Sociological Review,31(6), 713–724. Google Scholar

- Asakura, M. (2010). Position of work-life balance in the labor and employment law. The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies,52(6), 41–52. (in Japanese). Google Scholar

- Bharathi, S. V., & Mala, E. P. (2016). A study on the determinants of work-life balance of women employees in information technology companies in India. Global Business Review,17(3), 1–19. Google Scholar

- Block, R. N., Berg, P., & Roberts, K. (2003). Comparing and quantifying labour standards in the United States and the European Union. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations,19(4), 441–467. Google Scholar

- Block, R. N., Malin, M. H., Kossek, E. E., & Holt, A. (2006). The legal and administrative context of work and family leave and related policies in the USA, Canada and the European Union. In F. Jones, R. J. Burke, & M. Westman (Eds.), Work-life balance: A psychological perspective (pp. 39–68). New York: Psychology Press. Google Scholar

- Bloom, N., Kretschmer, T., & Van Reenen, J. (2011). Are family-friendly workplace practices a valuable firm resource? Strategic Management Journal,32(4), 343–367. Google Scholar

- Bloom, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2006). Management practices, work-life balance, and productivity: A review of some recent evidence. Oxford Review of Economic Policy,22(4), 457–482. Google Scholar

- Bourguignon, F., & Morrison, C. (2002). Inequality among world citizens: 1820–1992. American Economic Review,92(4), 727–744. Google Scholar

- Brougham, D., & Jarrod, H. (2017). Employee assessment of their technological redundancy. Labour and Industry,27(3), 213–231. Google Scholar

- Brougham, D., & Jarrod, H. (2018). Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA): employees’ perceptions of our future workplace. Journal of Management and Organization,24(2), 239–257. Google Scholar

- Chandra, V. (2012). Work-life balance: Eastern and western perspectives. The International Journal of Human Resource Management,23(5), 1040–1056. Google Scholar

- Crompton, R., & Lyonette, C. (2006). Work-life ‘balance’ in Europe. Acta Sociologica,49(4), 379–393. Google Scholar

- Darcy, C., McCarthy, A., Hill, J., & Grady, G. (2012). Work-life balance: One size fits all? An exploratory analysis of the differential effects of career stage. European Management Journal,30(2), 111–120. Google Scholar

- Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology,29(1), 94–122. Google Scholar

- Frey, B. S. (2008). Happiness: A revolution in economics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Google Scholar

- Frey, B. S. (2018). Economics of happiness. Cham: Springer. Google Scholar

- Gallie, D. (2003). The quality of working life: Is Scandinavia different? European Sociological Review,19(1), 61–79. Google Scholar

- Geurts, S. A. E., Beckers, D. G., Taris, T. W., Kompier, M. A. J., & Smulders, P. G. W. (2009). Worktime demands and work-family interference: Does worktime control buffer the adverse effects of high demands? Journal of Business Ethics,84(2), 229–241. Google Scholar

- Golden, L., Henly, J. R., & Lambert, S. (2013). Work schedule flexibility: A contributor to happiness? Journal of Social Research and Policy,4(2), 107–135. Google Scholar

- Golden, L., & Wiens-Tuers, B. (2006). To your happiness? Extra hours of labor supply and worker well-being. The Journal of Socio-Economics,35(2), 382–397. Google Scholar

- Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2014). New measures of the costs of unemployment: Evidence from the subjective well-being of 3.3 million Americans. Economic Inquiry,52(4), 1485–1502. Google Scholar

- Helpman, E. (2004). Mystery of economic growth. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Google Scholar

- Ikeda, S. (2010). Review of sociological research on work-life balance. The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies,52(6), 22–31. (in Japanese). Google Scholar

- Karkoulian, S., Srour, J., & Sinan, T. (2016). A gender perspective on work-life balance, perceived stress, and locus of control. Journal of Business Research,69(11), 4918–4923. Google Scholar

- Kato, T., & Kodama, N. (2018). Women in the workplace and management practices: Theory and evidence. In S. L. Averett, L. M. Argys, & S. D. Hoffman (Eds.), Oxford handbook of women and the economy (pp. 561–593). New York: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar

- Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review,20(4), 635–649. Google Scholar

- Kodama, N. (2007). Effects of work-life balance programs on female employment. Japan Labor Review,4(4), 97–119. Google Scholar

- Kyo, K., Noda, H., & Kitagawa, G. (2013). Bayesian analysis of unemployment dynamics in Japan. Asian Journal of Management Science and Applications,1(1), 4–25. Google Scholar

- Morikawa, M. (2017). Firms’ expectations about the Impact of AI and robotics: Evidence from a survey. Economic Inquiry,55(2), 1054–1063. Google Scholar

- Morozumi, M. (2008). Basic principles of work-life balance: A legal approach. The Journal of Ohara Institute for Social Research,595, 36–53. (in Japanese). Google Scholar

- Ochsen, C., & Welsch, H. (2011). The social costs of unemployment: Accounting for unemployment duration. Applied Economics,43(27), 3999–4005. Google Scholar

- OECD. (2011a). Divided we stand: why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD. Google Scholar

- OECD. (2011b). How’s life? Measuring well-being. Paris: OECD. Google Scholar

- Oshio, T. (2014). Determinants of happiness: Economics of subjective well-being. Tokyo: Nikkei Publishing Inc. (in Japanese). Google Scholar

- Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2011). Area-level income inequality and individual happiness: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies,12(4), 633–649. Google Scholar

- Oshio, T., & Urakawa, K. (2014). The association between perceived income inequality and subjective well-being: Evidence from a social survey in Japan. Social Indicators Research,116(3), 755–770. Google Scholar

- Ouchi, S. (2009). What labor law can do to achieve work-life balance. The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies,51(2), 30–41. (in Japanese). Google Scholar

- Sala-i-Martin, X. (2006). The world distribution of income: Falling poverty and convergence, period. Quarterly Journal of Economics,121(2), 351–397. Google Scholar

- Stutzer, A., & Lalive, R. (2004). The role of social work norms in job searching and subjective well-being. Journal of the European Economic Association,2(4), 696–719. Google Scholar

- Szücs, S., Drobnič, S., den Dulk, L., & Verwiebe, R. (2011). Quality of life and satisfaction with the work-life balance. In M. Bäck-Wiklund, T. van der Lippe, L. den Dulk, & A. Doorne-Huiskes (Eds.), Quality of life and work in Europe: Theory, practice and policy (pp. 95–117). London: Palgrave Macmillan. (Chapter 6). Google Scholar

- Tomlinson, J. (2007). Employment regulation, welfare and gender regimes: A comparative analysis of women’s working-time patterns and work-life balance in the UK and the US. The International Journal of Human Resource Management,18(3), 401–415. Google Scholar

- Vasumathi, A. (2018). Work life balance of women employees: A literature review. International Journal of Services and Operations Management,29(1), 100–146. Google Scholar

- Wattisa, L., Standing, K., & Yerkes, M. A. (2013). Mothers and work-life balance: Exploring the contradictions and complexities involved in work-family negotiation. Community, Work and Family,16(1), 1–19. Google Scholar

- Weil, D. N. (2013). Economic growth (3rd ed.). Boston: Addison-Wesley. Google Scholar

- Yamamoto, I., & Matsuura, T. (2014). Effect of work-life balance practices on firm productivity: Evidence from Japanese firm-level panel data. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy,14(4), 1–32. Google Scholar

- Yanadori, Y., & Kato, T. (2009). Work and family practices in Japanese firms: Their scope, nature and impact on employee turnover. The International Journal of Human Resource Management,20(2), 439–456. Google Scholar

- Yu, S. (2014). Work-life balance: Work intensification and job insecurity as job stressors. Labour and Industry,24(3), 203–214. Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Japan Economic Policy Association, Kokushikan University, May 2015. I am grateful to Professor Hiroyuki Kawanobe for constructive comments and discussions. Two anonymous reviewers have also offered helpful remarks, which have made this article more valuable and readable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- School of Management, Tokyo University of Science, 1-11-2 Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 102-0071, Japan Hideo Noda

- Hideo Noda